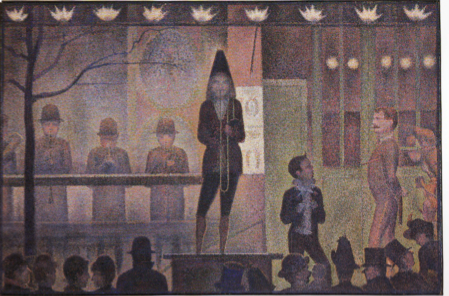

I recently added a painting, Fernand Pelez’s Grimaces and Misery, to the 19th century timeline (2nd half). Dating from 1888, it is an exact contemporary of Georges Seurat’s Parade de cirque (which I’ve also included below). Although there are obvious stylistic differences, the similarities in subject matter between the two paintings have been noted by art historians. It is interesting (from my viewpoint, at least) that both depictions include trombonists. The musicians are situated on opposite sides of the platform in two the paintings, with a trombonist replacing a clown in the center of Seurat’s image. They all look pretty gloomy. Art historian Robert Herbert, discussing these two paintings, explains, “The clown and the parade stand not for pure joy, but for the contrast between joy and sorrow, between the entertainer’s act and the reality of life behind the mask” (Herbert, Seurat 152). The musicians in Pelez’s painting are more intensely downtrodden.

1888—Paris, France: Fernand Pelez’s Grimaces and Misery depicts poor circus workers situated on a platform, including a group of three seated musicians (see above detail and full image; public domain) (Musée du Petit Palais, Paris).

1888—Paris, France: Georges Seurat depicts a circus trombonist in Parade de cirque (see above image; public domain). In contemporary photographs the circus that Seurat portrays, identified as the popular Cirque Corvi, reveals a trombone hanging from a pillar near its entryway. Advertisement posters of the time depict a clown standing on the central pedestal occupied by the trombonist in Seurat’s painting (Herbert, Seurat 137-143). An exact contemporary of Seurat’s work is seen in Fernand Pelez’s Grimaces and Misery, which depicts a similar scene, this time with two clowns on the central pedestal and three musicians, a clarinetist, trombonist, and ophecleidist, seated to the right of center (Herbert, Seurat 152).

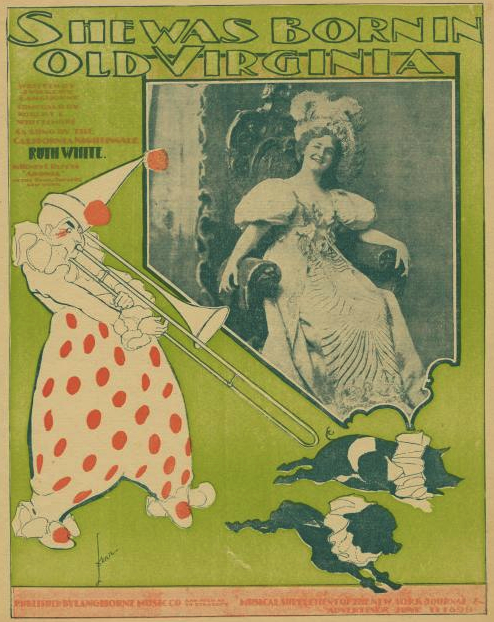

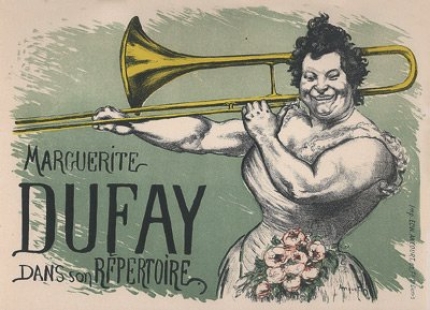

One more thing might be worth noting. As trombone images move from the intensely religious, particularly in the 17th century (1st half, 2nd half), to the many humorous depictions of the 19th century (2nd half), the association of trombones with clowns begins to take shape. It can be seen not only in the above two paintings, but in images such as the the Anquetin lithograph (below), the “Old Virginia” cover (below), and, later, even in solos like the famous Berio Sequenza V (1966).

.